National Aerospace Standards NSN Parts: NAS1352N04-5B - nas1352n04-6

Acknowledgements to Dr. Clifton Callaway, MD, PhD. Vice-Chair of the Emergency Department of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Credit must be given for his suggestions to the final edition of the manuscript.

The ability to accurately predict patient outcome after TBI has an important role in clinical practice and research. Prognostic models are statistical models that combine two or more pieces of patient data to predict clinical outcome and are likely to be more accurate than simple clinical predictions. 18 Furthermore, due to limited resources in underserved and austere environments, GCS is relied on as an accurate predictor of outcome and to determine resource allocation after TBI. 19 In this study, we investigated the effect of GCS score on mortality prediction, comparing patients with admission GCS scores of 13 classified as moderate (classic model) to patients with admission GCS scores of 13 classified as mild TBI (modified model).

The lack of overlap between ROC curves of both models reveals a statistically significant difference in their ability to predict mortality. The classic model demonstrated better GOF than the modified model. A GCS of 13 classified as moderate TBI in a multivariate logistic regression model performed better than a GCS of 13 classified as mild.

Third Evaluation adjustment for the presence of hypothermia, hypotension at admission, need for paralyzing drugs and intubation, screening for psychoactive drugs, and final diagnosis at discharge.

We have developed a comparative analysis in order to measure the effect of an admission GCS score of 13 classified as moderate TBI (classic model) versus an admission GCS score of 13 classified as mild TBI (modified model) in mortality prediction. We performed three comparisons between those logistic multivariable models with a major outcome using clinical and demographic predictors available in a state trauma registry. Our analyses show that an admission GCS score of 13 classified as moderate predicts mortality better than the modified model in TBI patients.

Hypothermia, hypotension, and hypoxia are associated with increased probability of death as secondary insults. 31 Hypothermia was defined as body temperature ≤ 35° degrees Celsius31–33 and hypotension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90mmHg.31,34 Unfortunately, hypoxia is not available in the PTOS database.

The odds of survival were fit into multivariate logistic regressions. Most of the variables included in these evaluations have been previously associated with prognosis in TBI, so we included all of them in the multivariable logistic regression analyses. Each of these predictors was evaluated for its contribution in both the classical and modified models. Findings are presented as odds ratio (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values. 39 We assessed both models’ prediction of mortality by sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and proportion of correctly classified cases. The models’ performance was evaluated with calibration and discrimination. Discrimination was defined as the ability of the models to accurately predict mortality and was evaluated using the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Calibration, defined as the ability of the models to accurately quantify the risk of mortality, was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemershow goodness of fit (GOF) test. 39,40 After these estimations, we tested different models with and without each of one of the predictors in order to see if there were any changes on the effect of both GCS classifications on the prediction of mortality. 40,41 Analyses were performed in STATA, Version 11 (Stata Corporation College Station TX). 39

Is GCS 3 dead

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Traditionally, the GCS classified TBIs as Mild (14–15), Moderate (9–13), or Severe (3–8). Based on the findings of the Canadian Computed Tomography (CT) Head Rule Study, Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) recently modified this classification so that a GCS score of 13 would fall within the mild category of TBI (Mild 13–15). 12–14 Multiple major organizations, including the Eastern Association of the Surgery of Trauma and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) use 13–15 to define mild traumatic brain injury. A recent study showed that a pre-hospital GCS < 14 accurately predicts the need for full trauma team activation and patient hospitalization after motor vehicle collisions; 15 however, there is no standardized approach regarding this classification and there is not enough evidence to support the necessity of this recent modification to the GCS.

TBI patients admitted to Pennsylvania trauma centers were identified from the PTOS using the Barell Matrix to categorize injury diagnosis. 21 We excluded patients with more than 48 hours between their injury event and admission to trauma centers to avoid diagnoses of late effect or late consequences of the primary injury event. The database uses diagnostic codes from the 9th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9), included in the CDC Case Definition for TBI based on case reports from coded death certificates or hospital discharge data: 22 800.0 – 801.9 (fracture of the vault of base of the skull), 803.0 – 804.9 (other and unqualified and multiple fractures of the skull), 850.0 – 854.1 (intracranial injury, including concussion, contusion, laceration, and hemorrhage), and 873.0 – 873.9 (other open wound of head). 23

GCS verbal subscore is 5

As a predictive instrument, the GCS works best if each of the subscales (eye, motor, verbal) is used as a separate predictor variable and is combined with other important predictor variables. It remains to be determined how to perform such a combination and which other variables should be combined to give adequate predictive power in terms of the evaluation of the effect of the modified GCS criteria48,49. In this study, we obtained all the predictive parameters of both multivariable models adjusting for important clinical predictors of mortality and adjusting for trend. The final results showed that the classic GCS model predicts mortality better than the modified GCS model.

GCS 8 survival rate

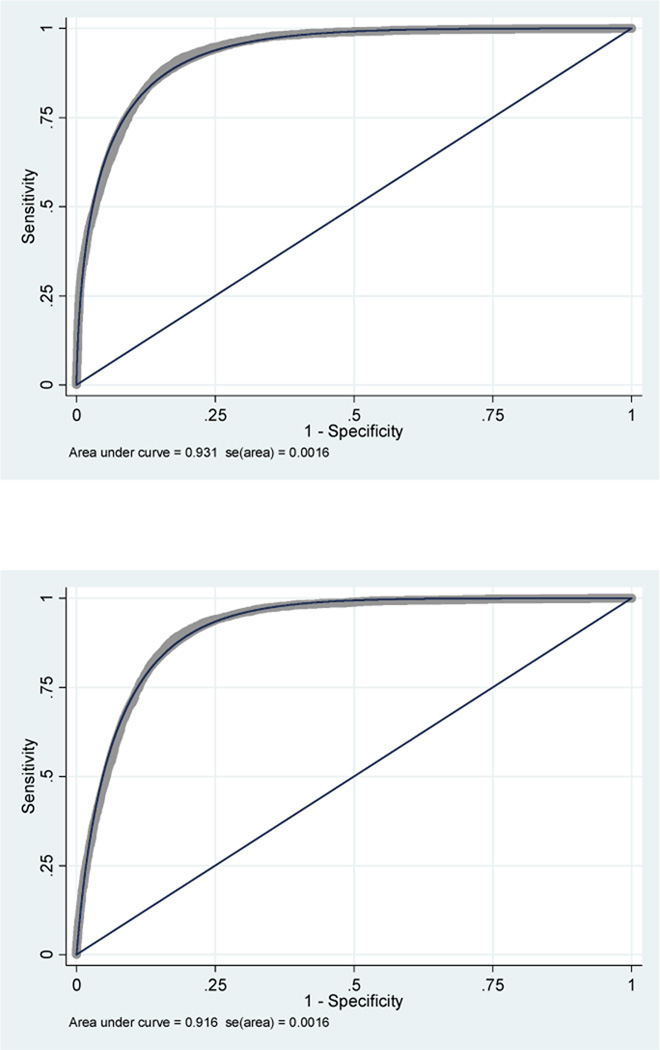

The results of sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and correctly classified cases are summarized in table 4. These parameters were better in the classic model GCS score of 13 category. The first evaluation of the AUC of the classic model was 0.922 (95 %CI, 0.918 – 0.926); the AUC of the modified model was 0.908 (0.904 – 0.912). The lack of overlap between confidence intervals for the two models reveals a statistically significant difference in their ability to predict mortality (figure 4). However, the two models showed poor calibration (p<0.001 for both models).

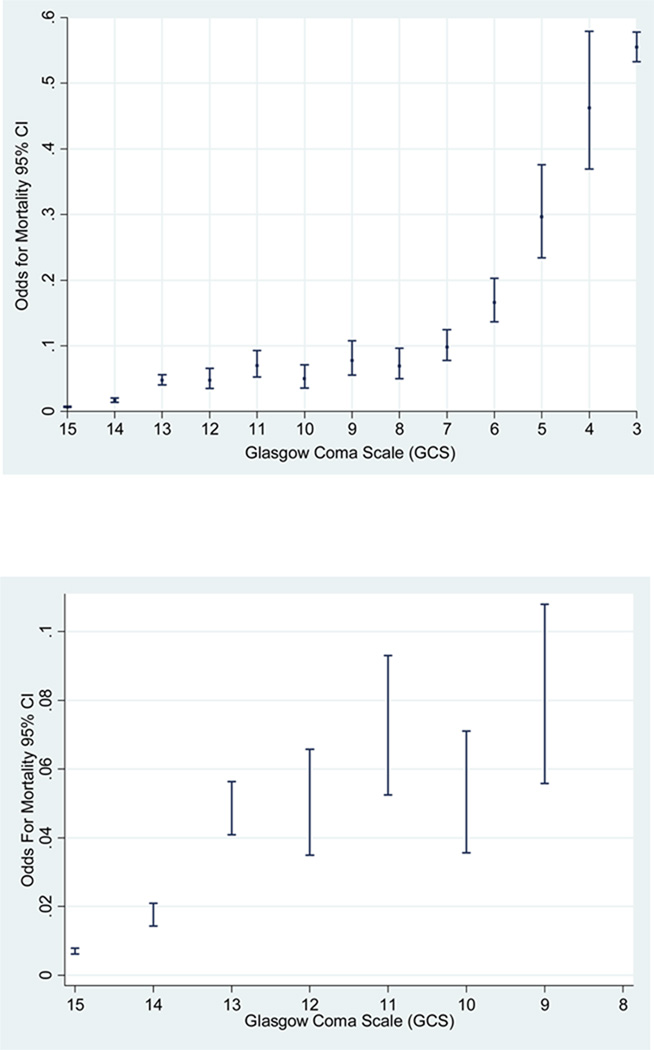

We plotted the odds of mortality and the GCS scores as continuous variable (score 15 to 3). We found that the odds of mortality for GCS score of 13 are closer to a GCS score of 12 rather than a GCS score of 14 (figure 2). In addition, we plotted the trend of mortality by TBI and we also found a significant trend in the odds of mortality across the years of the study (test score for trend of odds: chi2 = 70.21. Pr chi2 = < 0.001) (figure 3). This result leads us to take into account the effect of this variable prediction of TBI mortality in both the classic and modified models.

Other predictors such as length of stay, need for ICU and need for CT scan were analyzed but they were not significant results.

Most previous studies have suggested a linear relationship between GCS score and the odds of mortality. 3 Evidence found in two prospective series has shown that patients with a GCS of 13 harbor intracranial lesions at a frequency similar to patients with moderate head injury defined as GCS of 9–12. 16,17

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

GCS 15 meaning

Compared to the modified classification, the classic GCS model established an important difference in the proportion of mortality in patients with several predictors included in the analyses. Table 3 depicts the mortality proportions in the categories of classic and modified GCS classifications. We observed differences in mortality between patients who sustained traffic injuries, falls, and firearms injuries, between patients with the presence of penetrating and hemorrhage TBI and those with skull fracture, and between patients with hypothermia and hypotension at admission and the need for mechanical ventilation.

The association between hypoxia and hypotension and bad prognosis has been explored for several years. Miller et al. found that hypoxia and hypotension are highly related to a poor outcome following TBI. 43 Recent studies have found a greater detrimental combined effect of hypoxia, hypotension, and hypothermia on adverse outcome following TBI. 32,44 In this study, the inclusion of hypotension and hypothermia with other clinical predictors improved the discrimination and calibration of the logistic regression models. Unfortunately, we were not able to include hypoxia in the models because that variable was not in the dataset.

Glasgow Coma Scale

Our dependent variable was discharge status, categorized as deceased or alive. This outcome variable was evaluated to assess the effect of both GCS classifications and prognostic factors in TBI patients.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) classifies Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI) as Mild (14–15); Moderate (9–13) or Severe (3–8). The ATLS modified this classification so that a GCS score of 13 is categorized as mild TBI. We investigated the effect of this modification on mortality prediction, comparing patients with a GCS of 13 classified as moderate TBI (Classic Model) to patients with GCS of 13 classified as mild TBI (Modified Model).

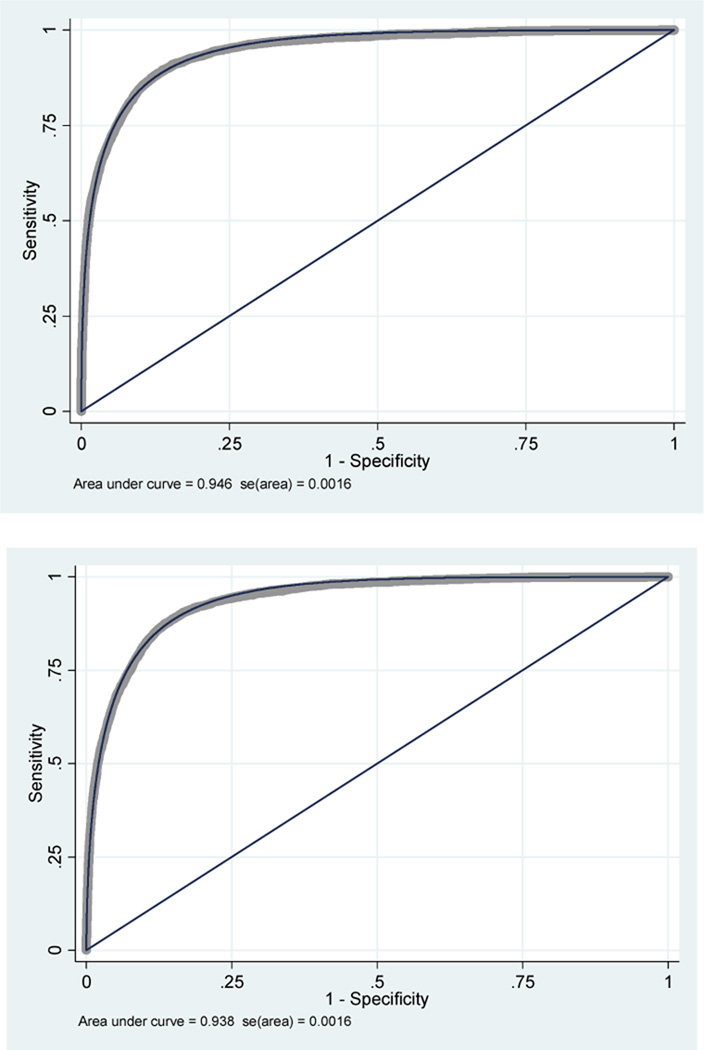

In the first evaluation, the AUCs were 0.922 (95 %CI, 0.917–0.926) and 0.908 (95 %CI, 0.903–0.912) for classic and modified models, respectively. Both models showed poor calibration (p<0.001). In the third evaluation, the AUCs were 0.946 (95 %CI, 0.943 – 0.949) and 0.938 (95 %CI, 0.934 –0.940) for the classic and modified models, respectively, with improvements in calibration (p=0.30 and p=0.02 for the classic and modified models, respectively).

The inclusion of hypotension and hypothermia was based on the results of McHugh et al. from the IMPACT study. The authors of this study performed a meta-analysis in order to establish the association between secondary insults (hypoxia, hypotension, and hypothermia) occurring prior to or on admission to hospital and 6-month outcome after TBI. The results of their analysis demonstrated that an increased pre-enrollment insult of hypoxia, hypotension, or hypothermia were strongly associated with a poorer outcome. 31

All the models depicted excellent discrimination and the third evaluation showed better GOF for the classic model. Increased age, the presence of hypothermia, and the need for mechanical ventilation have all been previously identified as predictors for poor outcome in patients with TBI. In addition, variables such as diagnosis at discharge and screening for drugs were important predictors that increased the discrimination and calibration of the models. 24,25,27,29,31–33,37,42

Corres. Author: Jorge Mena, Scaife Hall, Suite A-1305, 3550 Terrace Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, University of Pittsburgh, jhm26@pitt.edu

We performed a secondary analysis on 1998–2007 data from the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcome Study (PTOS) database, a trauma registry that contains trauma patients’ information from 31 accredited trauma centers in Pennsylvania. Patients between 18–65 years 20 of age who sustained TBI were selected to perform the comparative analysis between the two multivariate logistic regression models.

The Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation, Mechanicsburg, PA, provided these data. The foundation specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions. Credit must be given to the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcome Study (PTOS) as the source of data.

Continuous variables were compared according to the outcome with unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney test, according to their distribution. Categorical variables were compared by Chi2 test. 26 Proportions of mortality were calculated using denominators of the total number of TBI patients between 18–65 years of age.

The study sponsors had no role in the study design, in the data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

In the third evaluation, we added TBI severity according to the Barell Matrix, 21,22,28 the presence of hypothermia and hypotension at ED admission and the need for mechanical ventilation at the time the first set of vital signs were taken. We also included any positive screening for drugs either at the facility or prior to arrival at the trauma center. 29,30

GCS motor subscore is 6

For the classic model, we set the first indicator variable equal to 1 for GCS scores from 14 to 15 (mild TBI) and equal to 0 otherwise, and set the second indicator variable equal to 1 for GCS scores from 9 to 13 (moderate TBI) and equal to 0 otherwise. For the modified model, we set the first indicator variable equal to 1 for GCS scores from 13 to 15 (mild TBI) and equal to 0 otherwise, and set the second indicator variable equal to 1 for GCS scores from 9 to 12 (moderate TBI) and equal to 0 otherwise. The reference level for the dummy variables in both models was GCS scores from 3 to 8 (severe TBI).

The need for mechanical ventilation was defined as the need for intubation with or without the use of paralyzing medications at the time of the first set of vital signs assessment.35,36 Intubation with or without the use of paralyzing medications do not necessarily implicate the presence of hypoxia. We do not use these variables as surrogates of hypoxia. There are several studies and reviews that have reported intubation and induced paralysis as clinical confounders of the association between GCS and TBI mortality. Furthermore, the use of intubation with or without paralyzing medications may impair the assessment of the verbal response.10,30,37,38

In the third evaluation, the AUC of the classic model was 0.946 (95 %CI, 0.943 – 0.949) and the AUC of the modified model was 0.938 (95 %CI, 0.934 – 0.940). The 95% CIs were closer but still did not overlap each other. In addition, the classic model showed better calibration (p=0.298) than the modified model (p=0.02) (figure 6).

Third Evaluation adjustment for the presence of hypothermia, hypotension at admission, need for paralyzing drugs and intubation, screening for psychoactive drugs, and final diagnosis at discharge.

We analyzed 60,428 adult TBI patients out of more than 200,000 patients admitted to trauma centers in Pennsylvania. The mortality rate was 7.8% (figure1). The median age was 37 (inter quartile range [IQR]=25–49) and there was no difference in age between survivors and non survivors (p=0.885). We found a statistical difference in the severity of injury between survivors and patients who died (p<0.001). Most of the patients were male (72.5%). Road traffic crashes were the most common cause of injury (57.3%); the second most common cause was falls (20%). Table 1 shows the general patient characteristics.

We performed three multivariable predictive models. Table 3 depicts the OR for each GCS category in the three evaluations. Because we gave the baseline value to the category of severe TBI, all the ORs for the moderate and mild TBI are less than 1. We show that the ORs for moderate cases are significantly different in both multivariable models (Table 3).

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of disability, morbidity, and mortality world-wide and is responsible for a significant proportion of all traumatic deaths in the U.S.1 Every year, an estimated 1.5 million people die and hundreds of millions require emergency treatment after a TBI. Fatality rates and disability rates vary depending on the severity and mechanisms of the TBI, but the rates of unfavorable outcomes (death, vegetative state, and severe disability) following TBI can be higher than 20%. 2,3

GCS 14 meaning

The dummy variables of GCS scores that were constructed to perform the comparative analyses are depicted in table 2. Most patients had mild brain injuries (67.9% in the classic GCS model vs. 70.8% in the modified GCS model). The percentage of patients with moderate TBI was 10.4% in the classic GCS model vs. 4.8% in the modified GCS model. We found significant statistical differences between survivors and patients who died across the different levels in both the modified and the classic classifications of GCS dummy variables (p<0,001).

Glasgow Coma Scale ppt

This work was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, grant 1 D43 TW007560 01.

In the second evaluation with a dummy variable of the year of injury, the AUC of the classic model was 0.931 (95 %CI, 0.928 – 0.934) and the AUC of the modified model was 0.916 (95 %CI, 0.913 – 0.919). These AUCs were closer to each other but there was still a lack of overlap between 95% CI for both models, maintaining the statistically significant difference in their ability to predict mortality (figure 5). However, in both models, there was still evidence of poor calibration (p<0.001 for both models).

We selected adult TBI patients from the Pennsylvania Outcome Study database (PTOS). Logistic regressions adjusting for age, sex, cause, severity, trauma center level, comorbidities, and isolated TBI were performed. A second evaluation included the time trend of mortality. A third evaluation also included hypothermia, hypotension, mechanical ventilation, screening for drugs, and severity of TBI. Discrimination of the models was evaluated using the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Calibration was evaluated using the Hoslmer-Lemershow goodness of fit (GOF) test.

The selection of predictors was based on clinical considerations and literature review. We considered age, sex, cause of injury, injury severity score, presence of co-morbidities, trauma center level, and whether the patient had sustained isolated TBI, which is defined as no other injuries or no extra-cranial injuries with a maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score of 1. 24,25

Our study strengths are the use of a well described cohort of patients of a state wide trauma registry with over 10 years of data, a large sample size in relation to several clinical predictors and adjusting for the trend of mortality by TBI strengthens the internal validity of our study. Some criticism could be raised because of the pseudo scoring in significant numbers of intubated or aphasic patients and the fall of GCS score reliability to undesirable levels. There are several studies and reviews that have considered intubation and induced paralysis as main clinical confounders of GCS;10,30,36–38,45,46 some of them were included in our analysis, some others were not. We hypothesized that intubation and paralysis were likely to confound the association between the different categories of the GCS score and TBI mortality; therefore, we took into account these variables in the analysis as the need of mechanical ventilation. The PTOS belongs to accredited trauma centers only; therefore, TBI patients admitted and managed in other hospitals or in places without trauma systems were not part of the current analysis. However, several guidelines for prehospital TBI care highly recommend that emergency medical personnel transfer the patient to a trauma center when one is available. This is what usually occurs when a trauma system is in place and working appropriately. 47The use of GCS as a discriminative instrument is that the GCS has been shown to possess all the necessary clinimetric properties for head trauma patients if it is used by experienced or trained personnel. Prasad et al. found that the scale has a good sensibility and reliability; it has well-established cross-sectional construct validity and its predictive validity in traumatic coma, and when combined with age and brainstem reflexes, is good in the generating sample. However, the validity of GCS as a predictive and evaluative instrument, which is the primary purpose for which the scale was constructed, has not yet been adequately studied. 48

In conclusion, we have developed a methodologically valid, simple, and accurate comparison that does not support the ATLS recommendation to reclassify a GCS score of 13 as mild TBI. Our data shows that the classification of an admission GCS score of 13 as moderate TBI in a multivariable logistic regression model results in better performance and accuracy (discrimination and calibration). This analysis may complement the clinical decision making process. However, more studies are required in order to evaluate the implications of this new classification in the clinical scenario and to obtain reliable findings related to this important issue. Further prospective cohorts and cost effectiveness analyses are needed to improve the generalizability of the results. 41,46

We did not find an adequate goodness of fit for either model; therefore, we hypothesized that the mortality trend was an important confounder of the association between GCS and TBI mortality and could be a good reason for the lack of calibration. Hence, we added year of the injury as a dummy variable to adjust for this trend in both the classic and modified GCS models. 26,27. We still did not find an appropriate goodness of fit in this second evaluation, so we conducted a third comparison between the two models.

To evaluate the effect of the modified GCS criteria for mild TBI on mortality prediction, we developed three evaluations between the two prognostic models. In the first evaluation, we built models that included the clinical and demographic variables described above. We reviewed patients’ demographics, injury characteristics, and anatomical diagnoses for severity categorization and hospital information. In order to evaluate the change in effect for the prediction of mortality in TBI patients, we constructed two models with dummy variables, using GCS at admission to emergency room. The first model included the dummy variables of GCS scores of 13 classified as moderate TBI (classic model) and the second model included the dummy variables of GCS scores of 13 classified as mild TBI (modified model).

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was developed to describe level of consciousness in patients with head injuries. 4 This scale was created primarily to facilitate the assessment and grading of brain dysfunction severity and outcome in a multicenter study of severe brain damage. 5 GCS measures a TBI patient’s best eye, motor, and verbal responses and is a widely used and accepted prognostic indicator for both traumatic and non-traumatic altered consciousness levels. 6 The score has been validated for its inter-observer reliability, which improves with training and experience in different scenarios. 7–10 In addition, the GCS has been recognized as a reliable tool to monitor patients with TBI and to identify when their condition deteriorates. The scale is also an index of injury severity, since the scores are related to either outcomes mortality or disability.11

8613869596835

8613869596835